This article was originally published in www.t-nation.com.

T NATION recently ran a terrific article on how and why to do pull-ups. In this one, I want to tackle a subject that’s related, but different: how to build bigger, stronger lats.

If your lats have a natural propensity to grow, you don’t need to know much more than whatever you learned the last time you picked up Flex: do a lot of pull-ups, pulldowns, and rows, and make sure everyone can see your “intense” face when you do them.

The rest of us have to give the matter a bit more thought, which is where I come in.

I want to start with a look at what the lats actually do, including the fact that they’re a misunderstood and underappreciated part of your core. Next I’ll show you some tweaks that will make pull-ups and pulldowns more effective. And then I’ll get into some of my favorite lat exercises, which are effective and fun to do.

Too Big to Fail

Given how big these muscles are, and how important they are to a bodybuilder’s physique, you’d think the latissimus dorsi would get a lot more attention than they do. Instead, back-training articles tend to focus on neglected muscles like the middle traps and rhomboids, which until recently few of us considered as major contributors to strength, performance, or appearance.

Certainly, those muscles are important, but now it’s the lats that seem to be too small a part of the conversation.

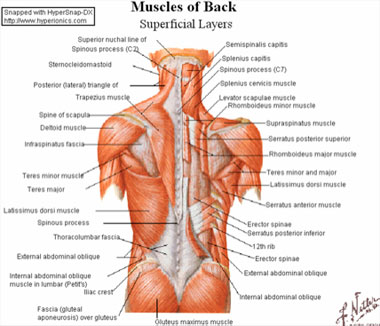

No other muscle has as much of a mechanical effect on as many joints as your lats. If you look at how the lats originate and insert, you’ll see that the lats are connected to your upper arms and your hips, with numerous attachments to your lumbar spine and ribs in between. It’s the only muscle with connections to your upper and lower body.

We all know that the relationship between your shoulders and hips is essential to your function and athletic performance. So strong lats are one of the big keys to improving your game as well as your appearance.

Because the connective tissues of your lats attach to your pelvis and lower spine, the lats are part of your core. If you train the upper- and lower-body functions of the lats simultaneously — as I show later in this article — you’ll end up with a stronger and more athletic middle body than you’d have if you focused your core training on abdominal and lower-back exercises exclusively.

Add Some More Pull to Your Pull-Up

If you’ve ever spent time looking at an anatomy chart, you’ve probably noticed the fibers of the lats run diagonally. And yet, exercises like pull-ups and lat pulldowns load the muscles in a vertical vector. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course — your lats are still doing the work even if the angle of pull doesn’t mimic the fiber orientation precisely.

But there’s a way to add a horizontal vector to the vertical line of pull, with the combination creating the equivalent of a diagonal. (I explained all this in A New Angle on Cable Training, my first article for T NATION.)

Pull the bar apart.

You can’t do this literally, of course. But if, while doing your pull-ups, you apply a force as if you were trying to pull the bar apart, you’ll add an extra challenge that should increase recruitment of your lat muscles.

When doing lat pulldowns, you can take a wide grip, holding the angled parts of the bar. Your lats will then pull your upper arms to your sides in a diagonal trajectory that lines up pretty well with the muscle fibers.

The Double-Duty Lat Pull — The Compound Row

Let’s return to the discussion of the lats as part of the core. Because the lats insert at the iliac crest — the top of your pelvic girdle — they play a role in back extension. And when you extend your back, you’re almost always tilting the top of your pelvis forward at the same time, exaggerating the arch in your lower back.

A lot of guys incorporate and exaggerate back extension when they do seated close-grip rows. That is, they bend forward on the negative and then lean backward on the concentric part of each repetition. My guess is that few T NATION readers do this, because more advanced lifters know that it puts unnecessary stress on the lower back, while at the same time taking work away from your upper-back muscles.

But there is a way to combine back extension with a close-grip pull without so much risk to your lumbar spine. It’s called the standing compound row.

Put the triangle extension on a high cable pulley, stand a few feet back with your feet shoulder-width apart and knees slightly bent, and bend forward at the hips so your torso and arms create a straight line with the cable. Straighten your hips as you pull the handle to your lower chest.

Because you’re standing, your lower back doesn’t go into as much flexion as it would if you were bending forward on a seated row. Plus, standing movements like this are always more functional. In sports, the actions requiring upper-body strength and power are almost always dependent on coordinated action with the core and lower body.

The Hardest Rollout in the World

Most of you are probably familiar with the rollout, and its many variations. (If not, Mike Boyle has a great introduction in T NATION.) And you probably know that the lats are involved in the exercise; when you pull the wheel or barbell back from the rollout position, you’re using your lats, triceps, and various shoulder muscles along with your core.

The heavy medicine ball roll uses the same idea, but it’s much, much harder.

You need a heavy, sand-filled medicine ball — 30 pounds or more. The heavier the ball, the harder it is. Start on your knees, with your hands on the ball and the ball beneath your shoulders. Walk it out as far as you can, then walk it back. That’s one rep. Do 3 to 6 sets of 5 to 8 rolls.

Fit to Fight — The Fighter’s Pulldown

Combat sports feature movements that aren’t seen in other sports. So when I train fighters, it makes sense to employ some specialized exercises. The fighter’s pulldown is one of my favorites because it mimics positions that are unique to martial arts: overhooking an arm, blocking a body strike, or getting an opponent into the plum clinch position.

If you have a dual-pulley lat pulldown station at your gym, you can alternate arms, as shown in the pictures to your right. If not, attach a D-shaped handle to the single pulley and work one arm at a time. The action is the same: you want to pull your elbow all the way down to your hipbone, combining the pulldown with a side crunch.

And if you’re not a fighter? Do it anyway. It’s a fun exercise to try, and it’s one of the few exercises you’ll do that incorporates lateral core training into a more traditional strength movement.

I like to use higher reps on this one. Try 1 to 3 sets of 12 to 20 reps per side.

The Primal Movement —The Pivot Prone Pulldown

Before you were born, you gestated with your knees up toward your chest and your spine curved. It gave you great leverage to kick your mother from the inside, and of course she appreciated that. So one of the most important movements you learned as an infant was how to extend your back and elongate the muscles on the front of your torso so you could push yourself up and look around at the world.

To do it, you had to pull your shoulder blades together, using your rhomboids, while lifting your arms to the sides with your elbows bent. If you hadn’t adducted your shoulder blades, you wouldn’t have had the strength to pull it off.

As adults, most of us spend so much time typing on keyboards with our shoulders hunched and arms forward that we start to lose strength and endurance in our rhomboids and lower traps — the muscles that pull our shoulder blades together and down.

That’s why my colleague Morgan Johnson, owner of Evolution Sports Physiotherapy in Baltimore, uses an exercise called the pivot prone pulldown, shown in a picture to your right. He uses it for injured clients and athletes, while I use it as a prehab exercise to keep my clients’ shoulders healthy.

You’ll need a dual-pulley lat pulldown machine for this one. Sit up tall, grab the handles with your hands facing out, pull your shoulder blades together, and then pull straight down to your sides. Since the low traps are predominantly endurance oriented, I like to use high reps, at least 12 per set.

Putting It All Together

If you do all of your upper-body pulls on one training day each week, you can put together these exercises in a program like the following:

| Exercise | Sets | Reps |

|---|---|---|

| 1) Wide-grip pull-up or lat pulldown | 4-6 | 6-10 |

| 2) Dumbbell bent-over row (1 or 2 DBs) | 3-4 | 6-10 |

| 3) Compound row | 2-3 | 8-12 |

| 4a) Heavy medicine-ball rollout | 2-3 | 6-10 |

| 4b) Pivot prone pulldown or fighter’s pulldown | 2-3 | 12-20 |

If you’re doing an Ian King split, with horizontal pulling one day and vertical pulling another day, you can do the compound row as a horizontal pull, and on the other day incorporate the wide-grip pull-up, pivot prone pulldown, and/or fighter’s pulldown. Then you could do the medicine-ball roll with your core exercises.

And if you’re doing total-body workouts, like a Waterbury system, do one of the pulling exercises each day.

But whatever you do, by all means show your lats some love. Give them challenges commensurate with their size and importance to your physique and athletic performance. Add exercises that incorporate their function as part of your core, without cutting back on work for their primary function: pulling your arms down to your sides.

The reward is a bigger, wider, thicker, and stronger back, and a more bad-ass overall physique. And if you don’t want that … well, let’s just say you’re unique among T NATION’s readers.

1 Comment

Great article!